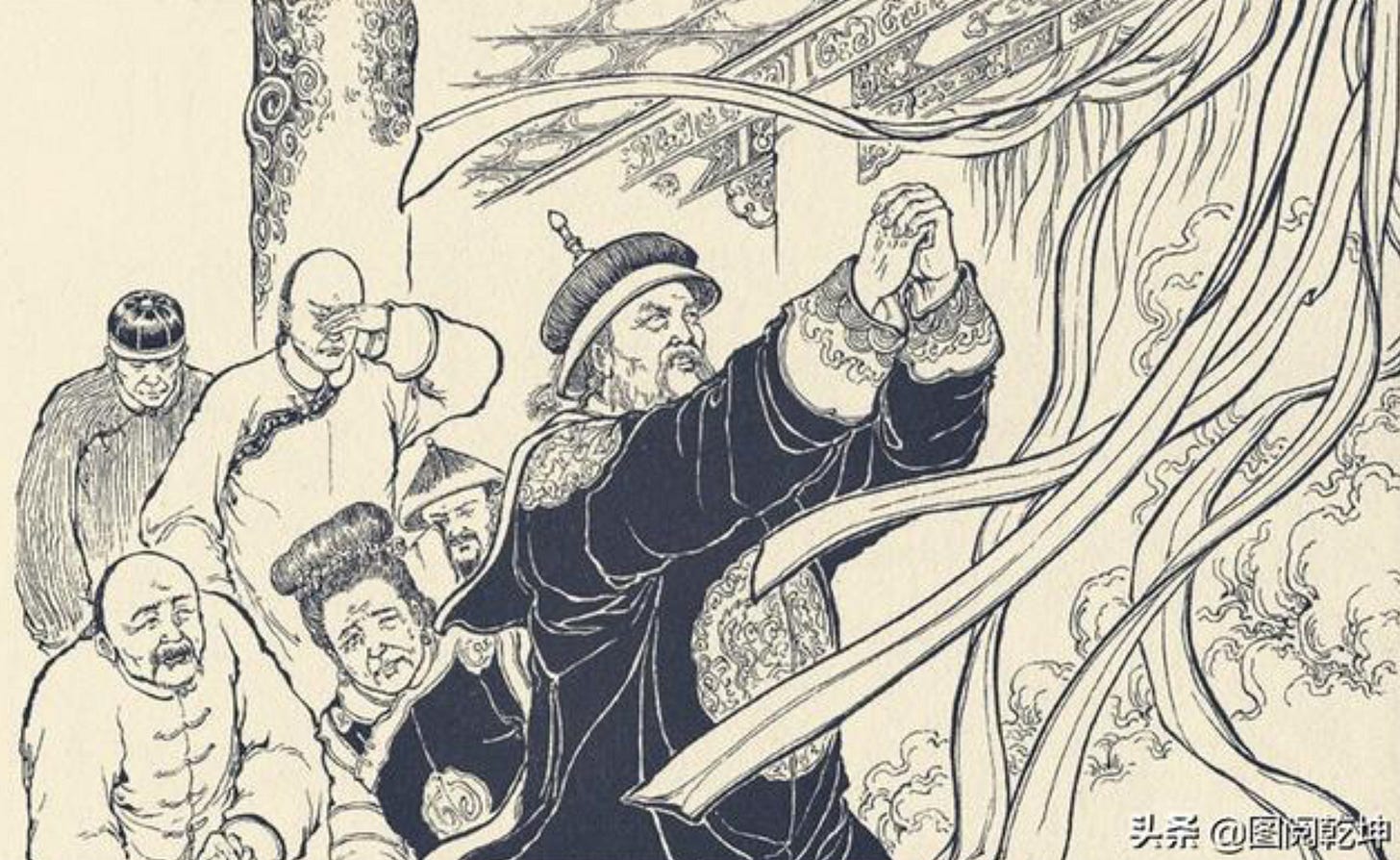

(Pictured: Shang Kexi dies in anger after his son, Shang Zhixi rebels against the Qing)

The most serious challenge the Manchu rulers of China faced in their first 200 years took place in 1673-1678, when the Three Feudatories declared they were going to reclaim China back from the Manchu.

The revolt by Wu Sangui, Geng Jingzhong, and Shang Zhixin started about 20 years after the Manchu had established what seemed like solid control over the former domains of Ming China. This revolt, which obviously failed because the Manchu remained in control of China until 1911, is one of the most confusing events in all of Chinese history - and that’s saying something!

The Sonoma Sage will now explain.

The Players

The Manchu. Under their warleader, Dorgon, the Manchu marched into Beijing in the summer of 1644 and declared the Ming Dynasty was over and the Qing now had the Mandate of Heaven. See my essay on Dorgon. See my essay on the Mandate of Heaven.

Wu Sangui - a former general of the Ming army who switched sides in May of 1644 and spent most of the next decade fighting against Ming loyalists. Wu was successful as a general. He won all his battles - though this sounds more impressive than one might think as he always had a bigger army. Wu led his soldiers all the way south to Rangoon Burma to fight and destroy the army of the last Ming pretender to the throne. In 1674 he was 62 years old and long past his prime.

Geng Jingzhong - the grandson of another Ming general who switched sides in 1632. Geng’s father, Geng Jimao was a very effective leader for the Manchu regime. In 1650 he captured Canton after a nine month siege (and then ordered the killing of every man and woman still alive in the city). His son, Geng Jingzhong, though he grew up in a military family, had not fought in any battles before he started his revolt in 1674.

Shang Zhixin - was the son of another Ming geneneral, Shang Kexi who switched sides and joined the Manchu in 1634. Shang Kexi commanded soldiers with some skill and though he was defeated in 1652, he rebuilt his army and drove the Ming loyalists out of southern China. By 1674 Shang Kexi was very old and very ill and he didn’t trust his eldest son, Zhixin, for good reason. Shang Zhixin was a very bad man - very very bad - who, like Geng Jingzhong, had no experience commanding soldiers in battle until 1674.

The Kangxi Huangdi (Emperor) - Just 20 years old in 1674, the Kangxi Huangdi had only taken power in 1669 and his abilities were unknown. History would later show that the Kangxi Huangdi was a man of enormous energy, wisdom, courage, and skill. He is now regarded as one of the greatest leaders in all of China’s history. No doubt Wu Sangui in 1674 regarded Kangxi as a young pup without knowledge or talent. This was a major error.

The Scene - 1673

The decades of war and internal revolt had been over since ~1660. Wu Sangui had pacified Yunnan province and was one of the richest men in China with a huge army under his command. Meanwhile, all the other great generals of the Manchu were long gone: Dorgon, Dodo, Bolo, Oboi - all the great men who had fought in countless battles were dead and buried. Now their sons were in charge, and they lived in huge palaces in Beijing, with a thousands servants and ten or twenty wives each. They spent their time waging vicious internal battles for status and power, which is why Dorgon, Dodo, Oboi, and all the others were dead. The great Manchu leaders from 1644 hadn’t died in battle, instead they had been assassinated (like Dorgon) or convicted of petty crimes and executed (like Suksaha).

Only Wu Sangui was still standing. Over and over his advisors asked (in private conversation): Why are you still working for these northern barbarians? China should be ruled by the Chinese. The Manchu are undisciplined, immoral, and too stupid to remain in power. They were lucky in 1644 but most of their victories since that year were won by Chinese generals, like you and Shang and Geng. Why shouldn’t you rule, instead of them?

The Spark

As mentioned above, Shang Kexi was old and ill in 1673 and he didn’t want his son to take over his position as governor of Guangdong province. He sent a formal request to the government in Beijing to be allowed to retire and specifically asked them not to appoint his son to his position. This makes sense.

What doesn’t make sense is that when Wu Sangui and Geng Jinzhong found out about Old Shang’s decision, they both submitted similar requests to Beijing, asking for permission to retire. The requests from Wu Sangui and Geng Jinzhong were totally insincere. Neither Wu nor Geng wanted to retire, they wanted to remain in power for the rest of their lives. What they were doing was pressuring the young Kangxi Huangdi to affirm their position in power. They wanted Kangxi to publicly state Yes, I want both of you to remain in control of your provinces.

Now, Kangxi knew that his government was sending millions of taels of silver to Wu Sangui every year (20 million taels in the year 1667, the first time Wu Sangui sent an insincere request to be allowed to retire). The Manchu government was spending more money supporting Wu Sangui’s army than they were spending on their own northern army. Kangxi sided with a minority of his top ministers and announced he was accepting Shang’s request and from this day forward, Guangdong province would be ruled just like all the normal provinces of China. Shang’s special Guangdong army was officially disbanded.

Wu Sangui decided that since Old Shang’s special status had been terminated, next it would be Geng’s province of Fujian, and then it would be him, in Yunnan. Thus, in late 1673, he rounded up and executed the Manchu loyalists in his government and declared he would retake China and restore the customs and laws of the Ming - but not restore the Ming Dynasty because he had helped to kill all members of the Ming royal family.

In Guangdong, Shang’s son Zhixin, found out what his father had done and quickly imprisoned his father and declared that he was joining Wu’s cause, but Zhixin did not accept Wu Sangui as the leader of Neo-Ming China. Instead, Shang Zhixin was apparently hoping to rule Guangdong as an independent king. This was idiotic. Guangdong didn’t have the geography or the manpower to maintain independence from the rest of China.

In Fujian, Geng Jingzhong also declared he supported Wu Sangui, but only in principal, as he too wanted to remain the warlord of an independent province. True, Fujian province is covered with hills and it has many major ports, but it would have been hard even for a great general to keep Fujian from falling to the certain attack from the Manchu armies coming from northern China.

Only Wu Sangui was in a good position. He ruled Yunnan which was a large and highly defensible territory. Yunnan had been an independent kingdom from 100 CE until the Mongols conquered it in 1250 CE (see the history of Dali). The Ming Dynasty controlled Yunnan thanks to the Mongol efforts - during the Yuan dynasty - to integrate Yunnan into the rest of China. Yunnan has defensible borders and still retained an independent identity, somewhat separate from the rest of China.

The War : 1674-1678

Prior to the war’s start, Wu Sangui exerted enormous influence over many provinces in southern and central China. This was due to repeated mistakes made by the Manchu leaders in Beijing in the years 1660 to 1673. In brief: the Manchu let Wu appoint provincial leaders and officials in the provinces which bordered Yunnan: Guizhou, Sichuan, and Hunan. They even allowed him to appoint officials in southern Gansu province. Most of the men Wu appointed supported him when he declared war on the Qing. The Manchu were able to swiftly take back control over Gansu but Wu started the war in control of much of southern China and the parts he didn’t control (Guangdong and Fujian) were nominally controlled by his allies.

Given the size of Wu’s army and his proven ability to command large formations of soldiers, the real threat to the Manchu would start if or when Wu ferried his army across the Yangtze river. Once across, the obvious goal for Wu was to capture Beijing. Although Wu Sangui brought his army to the northern border of Hunan (on the southern banks of the Yangtze) he waited to see what would happen elsewhere in China! This delay cost him the war.

While Wu‘s army waited, the Kangxi Huangdi responded with energy and the wise allocation of his resources. The Manchu took control over most of the boats on the Yangtze and they purged any and all Wu supporters in the lands north of the river. Kangxi realized that Wu’s allies, Geng and Shang were not really allies at all and he kept Wu’s army busy with modest raids on his army in Hunan while bringing Geng back under control. The Manchu army under General Giyesu (a great-grandson of Nurhaci) defeated Geng’s army which was advancing north along the coast, forcing it back into Fujian.

The pirate lord Zheng Jing, ruler of northern Taiwan and nominally a supporter of the Ming Dynasty, hated Geng and attacked Geng’s forces, taking two port cities cities in Fujian and raiding Geng’s capital, thus helping the Manchu. Odd behavior but pirates are not known for their long-term decision making skills.

Meanwhile, Shang Zhixin in Guangdong did almost nothing for Wu Sangui or his supposed ally to the north, Geng. Shang’s father died under house arrest, cursing his son for his treachery.

One looks - in vain - for a major battle between Wu Sangui’s army and the Manchu armies. Instead there were a series of minor actions and raids which Wu’s soldiers usually lost. Throughout 1675 the Manchu solidified their control over the north and built up ever larger armies facing Wu and Geng. Wu’s hopes that all of the Chinese would rise up against the Manchu remained merely a pipe dream.

1676, General Giyesu - after a stern threat from the Kangxi Huangdi - launched his long delayed invasion of Fujian and quickly captured Geng’s capital. Geng offered to rejoin the Qing in exchange for his life and that of his family. This offer was accepted, but the Manchu had no intention of honoring the deal. Instead, Geng’s army - with Manchu aid - recaptured the coastal cities the Pirate King had taken. In 1680, Geng was arrested and executed along with most of his extended family.

1677: An ally of Wu Sangui - Sun Yanling changed his mind and made plans to rejoin the Qing government. Before he could carry out his plan, Wu had the man assassinated. This did not improve Wu’s standing with his remaining allies. Shortly after the murder of Sun Yanling, Shang of Guangdong followed the example of Geng and rejoined the Qing government, though he did almost nothing for the Qing. Instead, Shang’s army remained in Guangdong, nearly inert. In 1679 he also was arrested and executed but because he had done so little during the war, some of his family and advisors were not killed, only exiled.

1678: Facing large Manchu armies on both of his flanks, Wu Sangui retreated to southern Hunan. Trying to shore up his failing reputation, Wu Sangui put on the robe of a Huangdi and claimed he now had the Mandate of Heaven. As Huangdi, Wu Sangui inspired very few new supporters. Instead, this decision was a fatal mistake because the Sonoma Sage believes this gave the Qing an opening to kill Wu Sangui via his new Imperial Eunuchs, which every Huangdi simply had to have. Whether it was a skillful poisoning operation conducted by eunuch assassins or just bad luck, Wu Sangui took sick and died less than six months after he put on the royal robes. After Wu’s death, the revolt was doomed. Wu’s sons had all died earlier, leaving a young grandson as the new Huangdi of Wu’s shrinking kingdom.

The Manchu armies, ably led by General Zhao Liang-dong, methodically took back all of Wu’s kingdom, culminating in a siege of Yunnan’s capital. After a six month siege, the city was taken and all of Wu Sangui’s remaining family were killed, along with nearly all of his advisors, his generals, and most of the scholars still alive.

Note: Two Manchu generals involved in the final phases of the war managed to steal the glory due to General Zhao. General Zhao went to the Kangxi Haungdi and made his case that he had been responsible the successes in the last years of the war. It took many years before the truth was finally clear and it wasn’t until the Qianlong’s reign - and many years after Zhao’s death - that General Zhao was properly recognized for his achievements.

Assessment

Wu Sangui was the wrong man to try and overthrow the Manchu government. He was too old in 1673 and, more importantly, he had done the bidding of the Qing for so long that no one could take his claim to represent the Ming seriously. After all, he had hunted down and personally seen to the execution of Zhu Youlang, the last and longest-fighting Ming pretender to the rank of huangdi. After being a general of the Qing, and taking so much money from them, as well as honors and wives, it was absurd for him to say I’m really a supporter of Chinese rule over China. Trust me! Wu Sangu was purely self-interested and everyone knew it.

The fact that Wu had no clear plan of action for his revolt is obvious in his treatment of his supposed allies Shang in Guangdong and Geng in Fujian. These two young men were clearly weak-links for his new state; both were unproven leaders with no military experience or - as it turned out - ability. If Wu Sangui had been a better general, he would have taken over Guangdong and Fujian in the early days of his revolt. Alternatively, Wu could have launched a lightning campaign to attack Beijing at the beginning of his revolt, crossing the Yangtze River in January of 1674 and marching to the walls of Beijing by early spring.

Wu Sangui should have known he was viewed as a traitor by most Chinese in central and northern China. For him to wait in Hunan province for uprisings in the north to do most of the work for him displays very poor leadership and worse insight into what the Chinese in central and northern China thought.

Wu Sangui lacked moral fitness for the job of Huangdi. The time to switch sides and join with the Ming was in 1652, when the Ming army under Li Dingguo actually defeated a Manchu army and recaptured the capital of Guanxi province - really the only significant victory for the Ming army during the entire war (1644 to 1660). Instead, Wu Sangui fought for the Manchu and was very well rewarded for his efforts.

The Manchu were quite Machiavellian in their conquest of China. They were happy to have Chinese generals conduct the major military operations in southern China against the remaining Ming loyalists. Chinese generals, like Geng Jimao and Shang Kexi were eager to prove their worth to the Manchu by their ruthless and bloody treatment of Ming loyalist soldiers. After the slaughter of nearly the entire population of Canton in 1650, Shang Kexi could expect little loyalty or support from the residents of that region for the rest of his life. Putting Shang in charge of that region was - in a sense - a form of punishment. Similar massacres had occurred on smaller towns in Fujian province, where Geng Jimao was assigned to rule, and in Yunnan, where Wu Sangui ruled.

The Manchu could afford to treat the people of northern China fairly well and gain a reputation for good government and even-handed justice, while the brutal measures employed in the south could all be blamed on Chinese generals. When these Chinese generals later thought about turning on the Manchu, who exactly did they think would support them?

To be fair, the Manchu could have lost the war to Wu Sangui. The armies that Kangxi sent against Wu Sangui and Shang Xhixin were mostly comprised of Chinese soldiers with small contingents of Manchu bannermen and Manchu officers. If the Chinese of northern and central China had hated the Manchu, these armies would have revolted and joined with Wu Sangui. The fact is the Manchu armies in the 1670s were both loyal and effective fighting for the new Qing government. Clearly, the Manchu had done a good enough job to have gained - in the eyes of the northern Chinese - the Mandate of Heaven.