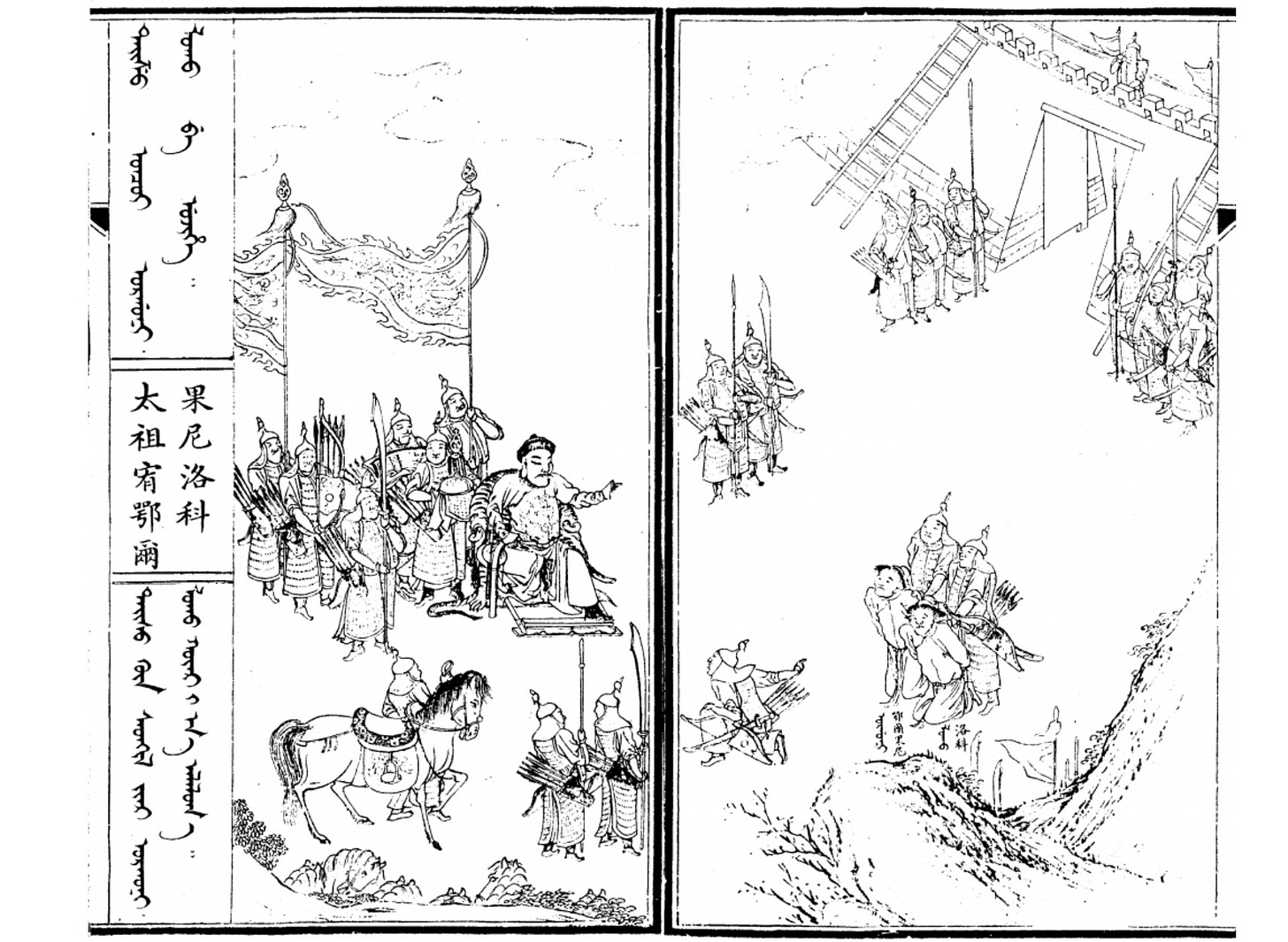

(Pictured: Nurhachi passing judgement over two enemy leaders, from the illustrated history of Nurhachi, now at the National Palace Museum in Taipei)

Part 2 - The Four Banners - 1600 to 1615

Part 3 - Eight Banners (1615-1650)

Part 4 - The Final Form of the Banners (1651-1900)

Introduction

For decades the Sonoma Sage has been puzzled about the Banners of the Manchu. Finally, the Sage has learned enough to explain it.

Nurhachi, the great founder of the Manchu state which later conquered and ruled China from ~1650 to 1911, invented the Banner system. Nurhachi started the Banner system in 1601 and it remained an important feature of Manchu society till 1911, more than 300 years in all. Note: the term Manchu was invented by Nurhachi’s successor Hong Taiji and applied to his nation in 1635. Nurhachi never used the term and in his lifetime his people were called the Jurchins.

The Banner system is credited with being the essential innovation which allowed the Manchu - a small, poor tribe living on the border of China - to conquer and rule China despite their tiny numbers. Considering how important the Banner System is, it surprises the Sage that the Banner system is so poorly understood.

One reason why the Banner system is poorly understood is because it transformed over time. It started as a military organization, changed into a political-social-military system, then changed again into something like the clubs which are found all over the USA in the 1900s such as the Rotary Club, the Lions, the Oddfellows, and others. The key difference being: you were assigned to a Banner at birth and it was rare for you to change banners.

Historical Background

To understand Nurhachi’s Banner system, we must understand Nurhachi’s background. He was born a member of the Aisin-Gioro clan. Aisin translates to Jin which means gold. Gioro is a small region amidst the rough borderland of China and Korea. In the distant past this region was claimed by the Han Dynasty, then it was part of the Kingdom of Gorguryeo, then it was part of the poorly understand state of Balhae, then it was part of the huge Khitan Empire.

In 1114, Aguda, a chief of the Wanyan tribe located in this same part of modern Heilongjiang province, as the Aisin Gioro tribe, revolted against the Khitan and, in an amazingly short time, he conquered most of it. Aguda founded the Jin Dynasty which proceeded to take control of half of Song Dynasty China in a war which lasted from 1125 to 1140. To rule over this huge territory, Aguda moved all his people south, nearly depopulating the lands he came from. Aguda’s tribe never returned home because they were nearly all killed by the Mongols when they destroyed the Jin Empire in a long war which ended in 1234.

It is no accident that the the Aisin Gioro are called the Gold, nor is it an accident that when they conquered China, they called themselves the Qing Dynasty (Qing and Jin are related words). In a very real sense, Nuhachi and his fellow tribesmen believed they were related to the Jin who captured China’s capital city in 1126 and forced the Chinese to pay tribute to them for 100 years.

It is also no accident that Nurhachi’s tribe believed that the Jin failed because they let wealth and power corrupt them and Nurhachi and his successors were determined to not make the same mistakes of his (theoretical) ancestors.

Nurhachi’s Early Life

Born the eldest son of the chief of the Aisin Gioro clan of the Jianzhou tribe in 1559, Nurhachi is one of the most remarkable men of his age. The Jianzhou were one of five major Jurchin tribes, along with the Yede, Hada, Ula, and Hoifa. Each tribe seems to have been roughly the same size, but the Yede tribe lived closest to the Ming border and could, at times, call upon the aid of Chinese soldiers.

Chinese sources say that Nurhachi spent some years in the household of the remarkably long-lived Ming commander of Liaodong, Li Cheng-liang, where Nurhachi learned to read and speak Chinese. The Manchu sources deny this assertion, but some modern historians (like Ken Swope) have sided with the Ming records. Both the Manchu and the Ming had self-interested reasons for making or denying the claim. Does the fact that Nurhachi’s father and grandfather were both killed by Li’s soldiers in 1582 weigh for or against the assertion? The Sage thinks the truth cannot be determined.

We do know that Nurhachi assumed control of his tribe at the age of 25 in 1583. He later recounted that his soldiers only owned 13 suits of armor when he became chief. The Sage assumes he meant metal armor and based on this remark, Nurhachi wanted more metal armor just like the elite Ming warriors he saw on his periodic tribute missions to Beijing. Nurhachi must also have noticed that some of the place guards of the Ming Huangdi wore color-coordinated uniforms; this became a feature of later Manchu armies. We know exactly the type of outfits worn by the Ming palace guards from this era, thanks to a detailed silk painting called The Departure Herald (which the Sage spent hours examining at the National Palace Museum in Taipei some years ago).

(A Ming cavalry unit, circa 1550, the rear-guard for the Huangdi’s army)

Back home, Nurhachi gained the allegiance of many previously unaffiliated clans due to his wisdom and his leadership in battles. His rise in power and status was not appreciated by Narimbulu, the leader of the Yede tribe. In 1590 the Yede raided some of Nurhachi’s settlements. Nurhachi didn’t back down from this confrontations with the Yede and tensions grew.

The normal state of affairs between the various Jurchin tribes was shifting alliances, with skirmishes, followed by marriages, followed by renewed conflicts. To a significant degree, this internecine conflict was deliberately fostered by the Chinese. Ever since the Han Dynasty fought its 40 year war with the Northern Barbarians, every Chinese government worked to prevent the various northern tribes from joining into a single state. This effort failed on several notable occasions such as in 900 CE, when the Khitan joined many tribes together and created the very powerful Liao Dynasty. Later it was the Jin state, not the Chinese, who failed to stop Genghis Khan from organizing all the Mongol tribes together. The Jin Dynasty paid the ultimate price for this failure as the Mongol Empire waged a war of annihilation against the Jin and killed nearly all of them.

The Ming Dynasty played this same game with the Jurchin tribes, trading with some, not with others, supporting first one chieftain and then another; giving ranks and titles to the leaders who seemed the most cooperative but always working to keep the tribes disunited. It is important to understand that the Ming didn’t hate the Jurchin tribes, as opposed to their hate for the Mongols. The Ming officially hated the Mongols from the very start of the dynasty and this attitude never really changed. By contrast, the Ming generally had good relations with the Jurchin tribes, some of whom claimed descent from the royal family of the Song Dynasty - an unprovable connection but actually quite likely given the history. The Jurchin tribes were considered semi-civilized barbarians, they lived in villages, they respected Ming military power, and they usually paid tribute every year.

Note: paying tribute to the Ming Huangdi once a year was highly beneficial. The Ming made it a point to give gifts to every group of ambassadors who came to Beijing. As a rule, the gifts the Ming gave were much more valuable than the tribute brought to the Ming court. The Koreans loved sending tribute missions to China as the people who went not only got to visit the great city and enjoy the nightlife, but they could make tidy sums of money by buying goods in the Beijing markets and then selling them when they returned to Korea. As one can imagine if you know any Koreans, they loved buying Chinese books and ink. We know Nurhachi made the 800 mile journey to Beijing on several occasions. The Sage imagines that that Nurhachi bought Chinese armor and swords but this may not have been possible.

The Japanese Invasion of Korea - A Hidden Opportunity for Nurhachi

In 1592, the Japanese invaded Korea and one of their cavalry units crossed the border into Jurchin territory. They fought with one of the Jurchin tribes, retreated, and never crossed the border again. It seems most likely that the Japanese ran into Nurhachi’s army and were defeated because a few months later, Nurhachi went to the Chinese general assembling his troops at the Yalu river - Li Ruson - and offered to join with the Ming in their counter attack on the Japanese.

The Ming were willing to accept Nurhachi’s offer but the Korean government, almost in exile on the Korean side of the Yalu river, did not like the idea and so Nurhachi was thanked and asked to guard the border and destroy any further Japanese incursions. In a very real sense, the Chinese regarded the Jurchin border with Korea as the Ming border with Korea, thus Nurhachi was defending their border from the Japanese.

Looking back on the decision to not let Nurhachi join the Ming army’s offensive against the Japanese, the Sonoma Sage thinks this was a mistake by both the Ming and the Koreans because if Nurhachi had died fighting the Japanese, or if he had lost many of his soldiers in the war, then the Manchu would never had conquered China, nor would they have forced Korea to become a tributary state. In fairness, no one could have predicted that result in 1592.

Given that Nurhachi had fought the Japanese and was willing to join in the counter-attack against them in late 1592, it is likely that Nurhachi was able to outfit his soldiers from 1592 to 1599 with surplus armor and weapons from the Korean war. A large quantity of military equipment was available for sale in Korea at this time thanks to the massive flow of war materials to the Ming & Korean army from China. In addition, large quantities of Japanese weapons and armor were captured from the Japanese as they retreated back to Pusan in 1593 and again in the last months of the war in 1598. Neither the Ming army nor the Korean army would have wanted their soldiers to wear Japanese armor or use Japanese weapons, but Nurhachi would have had no such qualms. The Sage guesses that Nurhachi was best positioned of all the Jurchin tribal leaders to acquire weapons and armor because he was seen by the Ming military as a military ally.

In 1593 Nurhachi came under a combined assault from all four of the other Jurchin tribes. This coalition was led by Narimbulu, chief of the Yede. Joining him in the attack on were several small Mongol clans from the grasslands around modern-day Harbin. Narimbulu’s intent was to destroy Nurhachi’s growing power before it was too late.

Outnumbered and attacked from both east and west, Nurhachi and his army retreated and then fought a critical battle at Mount Gure. This was likely win-or-die for Nurhachi and his warriors. Remarkably, Nurhachi won a total victory, killing several of Narimbulu’s generals and capturing others. This victory made Nurhachi the most feared and respected of all the Jurchin tribal chiefs. Because he was pushed to the brink of death, Nurhachi harbored a hate for the Yede tribe from then on and he waged war on them three times, finally conquering them in 1619.

After his great victory at Mount Gure, several Mongol chieftains allied with Nurhachi - at least in times of war. They called him a Khan and to strengthen the relationship Nurhachi married at least two Mongol women, beginning a practice which the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan were to follow for the next 200 years. Soon Mongol warriors became permanent additions to Nurhachi’s army and so, his Jurchen tribe transformed into a multi-cultural collection of Jurchins, Mongols, with some Chinese and Koreans added in.

The Ming government continued to support Nurhachi as the war in Korea simmered from 1594 to 1597. In 1595 the Ming gave him the highest title ever given to a Jurchin leader: Dragon Tiger General. [The Sage must confess he would have loved being given that title.]

When the Japanese finally fled Korean territory in 1598, the Ming turned their attention away from the region and Nurhachi decided he could safely subdue the other four Jurchin clans. First, he attacked the Hada tribe in 1599 and forced their surrender by 1600. From then on, the Hada tribe was part of Nurhachi’s new kingdom.

This is when Nurhachi decided to create the Banner system.

See Part 2 - The Four Banners of Nurhachi