New Research Finding: The Temple of Wu

The Wu Miao - state sponsored temples to men who exemplify Wu (武)

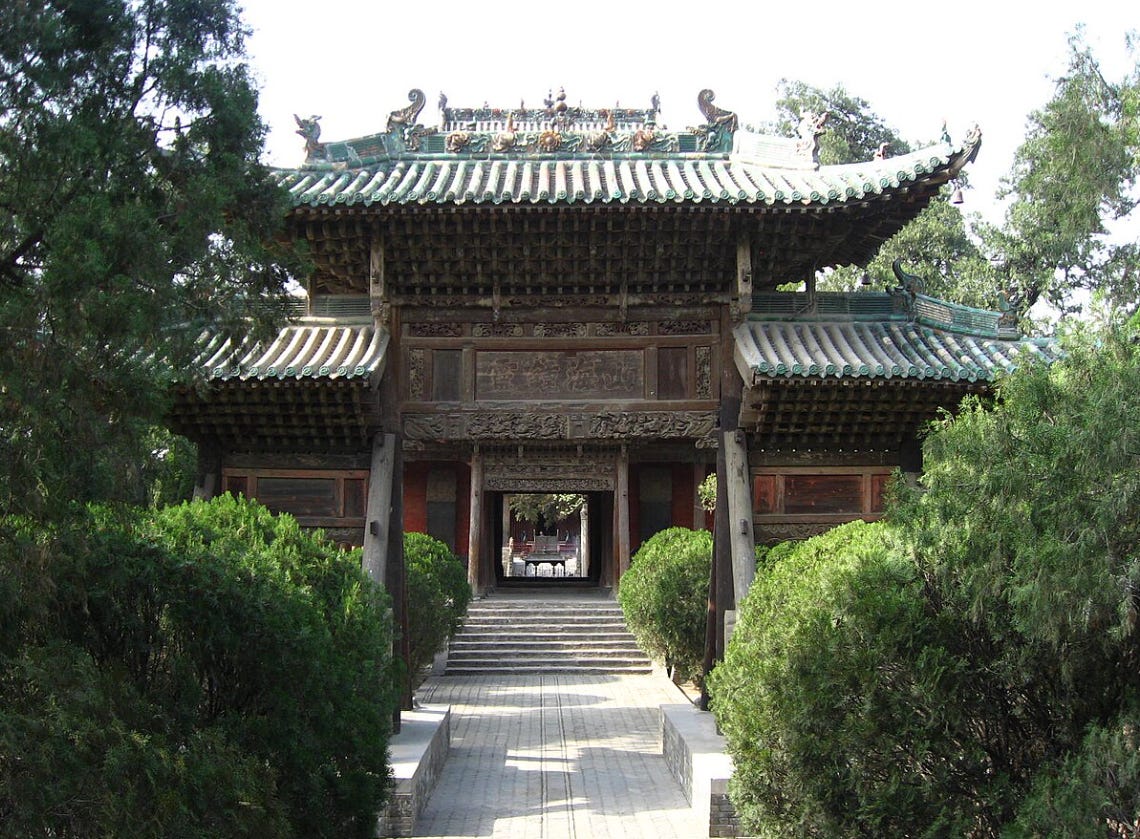

(The Guandi Temple in Shanxi, at Yuncheng City - photo from Wikipedia)

This is a guest post from my friend and co-author Colin Glassey. This describes an interesting discover he made about Chinese culture which I felt should be shared. - Sonoma Sage.

The Ministry of Rites in China not only developed and maintained Temples to Wen (文) (meaning literature or culture) but they also developed and maintained temples to Wu (meaning martial values). This gave official sanction within the Chinese state religion to the ideal that both literature and war-strategy were necessary for the preservation of the nation.

This knowledge that the Ministry of Rites officially supported the values of Wen and Wu and that a hundred men in Chinese history were honored for their martial abilities was lost over time, doubtless because the Qing Dynasty had their own non-Chinese cultural ideals about military virtue and thus the Chinese exemplars of Wu (martial valor or statecraft), meant very little to them.

When the Europeans studied China, starting around 1850, they failed to notice the Temples of Wu as by this era, the few surviving temples were now dedicated to the worship of Guan Yu, and were referred to as such by the Chinese. A few Guandi Temples (temples dedicated to the worship Guan Yu) still exist in China today but their true origin has been lost, until recently.

Acknowledgements: I’d like to thank my friend 秀才紫洞 (Scholar of the Purple Grotto) for setting me on this path. I’d also like to thank Fmzjf and a few others at the Chinese language Wikipedia for assembling the list of honored exemplars of Wu.

The Ministry of Rites

It is well understood that the Ministry of Rites was the most prestigious of the Six Ministries in the Chinese government. The staff of Rites presided many rituals, in every month throughout each year. Some of these rituals were described by Professor Romeyan Taylor in his chapter Official Religion of the Ming (Cambridge History of China, Vol. 8, Book 2). However, what he described was the rituals conducted by the Huangdi (Emperor) or his representatives and the evolution of those rituals over the course of the Ming Dynasty. Professor Taylor did not describe all the things which the Ministry of Rites did, which included: supervising all the various Temples to Wen, conducting the final stages of the Imperial exam, and managing visits by delegations bringing tribute to the Son of Heaven, the Huangdi.

The Temples of Wen — The Kong Temples

Starting around 400 AD, temples dedicated to Confucius and the other great sages of Chinese history began to appear. Early in the reign of Taizong of Tang (ruled 626-649 AD), he declared that every prefecture should have a Wen Miao, a temple dedicated to the great sages of China. It is believed that by the end of his reign there were some 1,100 Wen Miao built and staffed. The list of men who were honored in the various Wen Miao is large and apparently it was not fixed, with different temples honoring different men. However, Confucius and the four sages - Mencius, Xunzi, Yan Hui, and Zisi - were always at the front rank.

Over time the Temples to Wen became synonymous with the chief man who was honored at the temple: Confucius. Thus, in the Song Dynasty, the Temples of Wen were nearly all renamed to Kong Miao (孔庙) (i.e. Temples to Kong, the family name of Confucius). In 1800 there was a Kong Miao in every prefecture of China (equivalent to a county) with a total of more than 1,500. Today, more than 500 remain.

Kong Miao, from the Song Dynasty onwards, contained the following: a campus with walls all around. Inside was a courtyard and a hall for ceremonies. There were several halls for lectures (usually three), a library, a print shop, a dormitory for students who did not live close by, offices for the teachers, a kitchen, an herb garden, a pond for fish, and an archery range (see John Chaffee’s chapter Song Education, pg. 303, Cambridge History of China, Vol 5. Book 2).

Kong Miao were far from the only locations where students were taught. There were many private tutors in Chinese history. There were tens of thousands of small schools at various times, found in nearly every town and city. Also, there were a number of Academies such as: White Deer Grotto (near Luoyang), Yuelu Academy (near Changsha), Songyang Mountain Academy (next to the Shaolin Temple and not far from Luoyang), the Stone Drum Academy (in the middle of Hunan Province), Dragon Lake Academy (Long Tan Xue Yuan, also in Hunan), and Dragon Gorge Academy (Long Xia Xue Yuan, near Canton).

The large provincial Kong Miao always had an associated examination area (Kaopeng 考棚), used for the Imperial exams. Two levels of the exams were held at the Kaopeng:

The Yuan Shi ((院试), held once or twice a year. The men who passed the Yuan Shi exam were given the title Xuicai (秀才) (cultivated talent) and such men were allowed to be teachers and clerks for officials, but they were generally not allowed to hold government positions in their own right.

The Xian Shi (乡试) - the Provincial Exam - held once every three years, in the 8th month. The few men who passed the Provincial Exam were given the title Juren (举人) (recommended man) and these men were allowed to go to capital of China and sit for the Ming Shi (会试) (Capital Exam). The men who passed the Ming Shi were given the title gongshi and they were encouraged to sit before the Huangdi and answer his questions. Those who passed this final test (and nearly every man did pass) were called jinshi (recommended men).

The Wu Miao

So far as we can tell, there were no temples to the great military leaders in Chinese history until 731 AD. In that year, Xuanzong of Tang (r. 711-756) told the ministry of rituals to begin ceremonies dedicated to honoring the great military leaders and strategists of the past. The ministry officials subsequently presented a list of eleven men who they felt were worthy of being honored in the same way as Confucius and the four sages were worshiped.

Xuanzong approved the list and apparently had temples dedicated to honoring Wu built in a number of cities, not just in the capital of Chang’an.

Here is the list of the eleven men who were selected for inclusion in the first Wu Miao:

1. Jiang Ziya https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiang_Ziya

Jiang Ziya worked for the last ruler of the Shang dynasty, King Zhou of Shang (a tyrant who spent his days with his favorite concubine Daji and executing or punishing officials). After faithfully serving the Shang court for twenty years, Jiang feigned madness in order to escape court life. He later helped King Wen of Zhou and then his son defeat the Shang. Jiang Ziya is the supposed author of the Six Secret Teachings, however, modern historians are not sure that Jiang Ziya was real.

2. Zhang Liang - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhang_Liang_(Western_Han)

(Leader of the Right Side of the Temple)

Life: 251 BC - died 189 BC (age 62). He is also known as one of the Three Heroes of the early Han dynasty (漢初三傑), along with Han Xin (韓信) and Xiao He. Zhang Liang contributed greatly to the establishment of the Han dynasty.

Zhang Liang tried to kill Qin Shi Huang, and failed. He was later (supposedly) given a book titled The Art of War by Taigong (太公兵法) and Jiang Ziya. In 209 Zhang Liang became an advisor to Liu Bang and supported Liu Bang’s war against the Qin and then against another rebel: Xiang Yu.

3. Bai Qi https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bai_Qi (Leader of the Left Side of the Temple)

Life: 332 BC - 257 BC. A key general of the Qin, Bai Qi served as the commander of the Qin army for more than 30 years, earning him the nickname Ren Tu (人屠 : human butcher). According to the Shiji, he captured more than 70 cities from the other six states, and he was never single defeated throughout his military career. He was instrumental in the rise of Qin as a military power and the weakening of its rival states, enabling Qin's eventual conquest of them. He is regarded by Chinese folklore as one of the four Greatest Generals of the Late Warring States period, along with Li Mu, Wang Jian, and Lian Po.

4. Han Xin https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_Xin

Life: Active 208-196 BC. One of the Heroes of the early Han dynasty" (漢初三傑), along with Zhang Liang and Xiao He. Han Xin was renowned for his exceptional strategic intellect and tactical mastery. He used deception, maneuver, and tricks on the battlefield. Several of his campaigns became standard examples of great leadership. Han Xin's expanded upon the teachings of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, and some of his tactics gave rise to classic Chinese idioms. Supposedly never defeated in battle.

5. Zhuge Liang - My friend the Sonoma Sage has already discussed Zhuge Liang and the man himself is quite famous.

6. Li Jing https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Jing_(Tang_dynasty)

Life: 571-649 (at age 77). A general, strategist, and writer who lived in the early Tang dynasty and was most active during the reign of Taizong of Tang. In 630, Li Jing defeated the Gokturks, led by Jieli Khan, with just 3,000 cavalry soldiers. Li Jing and his colleague Li Shiji are considered the two best Tang generals.

7. Li Shiji https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Shiji

Life: 594-669 (age 75). Li Shiji was initially a follower of Li Mi, one of the rebel rulers rebelling against the Sui dynasty, and he submitted to the Tang Empire along with Li Mi. He later participated in destroying Xu Yuanlang and Fu Gongshi, two of the Tang Empire's competitors in the campaign to reunify China.

During the reign of Taizong of Tang, Li Shiji participated in the wars against the Gokturks and Xueyantuo, allowing the Tang Empire to become the dominant power in eastern Asia. He later served as a chancellor.

During the reign of Taizong’s son, Gaozong, he served as chancellor and the commander of the army against Goguryeo, conquering it in 668. He died the next year.

8. Sima Rangju https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sima_Rangju

Life: 900 BC? 800 BC? - He served in the State of Qi, defending it from the states of Jin and Yan, was later the Minister of War. Little is known about his life due to the lack of historical records. His works were later composed into a book called The Methods of the Sima. He was highly praised by Sima Qian, the great Chinese historian.

9. Sun Tzu - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Tzu

Life: 544-496 BC (age 47). Sun Tzu is quite famous in the USA and Europe because of his book The Art of War.

10. Wu Qi - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Qi

Life: 440-381 BC. Wu's reforms, around 390 BC, were aimed at fixing the corrupt and inefficient government of the kingdom of Wei (ancient). His military treatise, The Wuzi, is included as one of the Seven Military Classics.

11. Yue Yi - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yue_Yi

Life: Active 315-300 BC. Military leader of the State of Yan. He forged alliances with the states of Zhao, Wei, Chu, Han and Qin against Qi. He led the allied armies and crushed Qi. The cruel king of Qi was driven out, and, except for two cities, all of Qi was conquered. See History of the Warring States (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhan_Guo_Ce).

Comments on the Initial List of Wu Men

There is only one man chosen from the years 180 BC to 630 AD: Zhuge Liang. This is 800 years of continuous warfare and yet only Zhuge Liang was deemed significant? The obvious missing commander is Guan Yu, along with all the other great commanders from the Three Kingdoms period, not to mention all the generals who fought for Wu of Han, and who led armies during the Six Dynasties (230-580 AD).

Why make the Wu Miao in the First Place?

Until we find the actual records from 1,300 years ago here is what I can say:

Prior to 731, the Tang had a period of enormous military success. From 628 AD when they fought off a Tibetan invasion, till 668 when they conquered Goguryeo, the Tang armies had been victorious most of the time. Then, from 680 (under Wu Zetian’s despotic and unprincipled rule) till 730, Tang military forces had been defeated by Tibetans, Western Turks, and the Khitans. The military prowess of the Tang seemed to be in terminal decline. Reversing this trend was clearly a matter of national security.

The Chinese men who joined the army were no longer good warriors. They panicked under attack, the Chinese cavalrymen were inferior to the northern barbarians, and the brilliant strategies created by Tang officials all failed to produce victories. The martial qualities of the average Chinese solider was noticeably lacking by 720.

Xuanzong himself entrusted more and more of his army to the command of non-Chinese men such as An Lushan, Li Baoyu, Li Guanbi, Geshu Han, Gao Xianzhi, and many others. This policy proved disastrous when the An Lushan revolted and was able to convince many of his fellow Sogdians / proto-Mongol warriors to join him in an effort to conquer the militarily weak Tang Chinese. These barbarian generals nearly succeeded.

Given all these factors, it is no surprise that Xuanzong thought that what might be missing was martial spirit in his Chinese soldiers, and clearly his Chinese generals could use more knowledge about tactics and stratagems for winning wars.

Looking at the list of the eleven men selected for the Wu Meio, more than half were writers (or supposed writers) of military treatises. The Six Secret Teachings of Jiang Ziya was thought to be the oldest book of military knowledge, thus Ziya was the most highly venerated, even though his actual military campaigns are not described in any text. For all we know today, Ziya may not have ever led warriors in battle. In fact, Jiang Ziya may be a purely mythical figure.

The next oldest book was The Methods of the Sima by Sima Rangju. Unfortunately, that book which was known to have had 155 chapters, was now sadly reduced to just five chapters in the Tang Dynasty (and no copies of the original have ever been found).

Sun Tzu’s Art of War had survived intact and while some of his lessons of war seem trite, his book seems to have been regularly consulted by the staff in the Ministry of War.

The Wuzi by Wu Qi was likely written a bit later than Sun Tzu but large sections of it were missing by 730 AD (and have not been found subsequently).

The famous commander (and #2 man in the Wu Meio) was Zhang Liang and a book associated with him is called Three Strategies. That book was largely intact but it is mostly a book of Daoist philosophy instead of military strategy and tactics with the result that it was not actually useful to would-be generals faced with real problems of supply, leadership, tactics, etc.

The other men, Bai Qi, Han Xin, Yue Yi, and the two Tang generals: Li Jing and Li Shiji really did lead victorious armies in battle and they were worthy of being emulated. Two hundred years later, a book attributed to Li Jing became known to the Song, called Tang Taizong’s Thoughts on War. Initially dismissed as a forgery, the consensus is that the book is real and so Li Jing is both a great commander and a writer of a military classic.

The Role of the Temples of Wu

My guess is that the Wu Miao served an analogous role to the Wen Miao; meaning the temples were training centers for future Chinese military officers. Although not well documented, it is a fact that would-be Chinese military officers had to pass various tests to be admitted as commanders of soldiers in the army.

We know the tests consisted of proficiency in riding a horse, being able to hit targets with a bow and arrow, mastery of several melee weapons, and some knowledge of reading and writing. It is safe to assume future officers were also tested on their knowledge of some of the classic texts of warfare. It is highly likely that all of these skills were taught at the various Wu Temples across the nation. Given the limited supply of men who knew the basics of fighting in China, it is likely that Temples of Wu were located next to large military bases, in addition to the capital.

I assume that having created the list of eleven men of Martial Skill, the Ministry of Rites handed off supervision of performance of the rituals to the Ministry of War, but I don’t know. It is a fact that the Ministry of Rites was in charge of supervision of the final Civil exams (the Ming Shi and the Exam by the Huangdi). As a consequence, it seems likely that the Ministry of Rites would also supervise the examination of military officers who sought promotion to the highest ranks (Colonel and General) but again, this is not documented in any book I have read.