How The Ming Tried to Create An Effective Military

Part 2 of the Chinese Approach to Keeping Control Over the Military

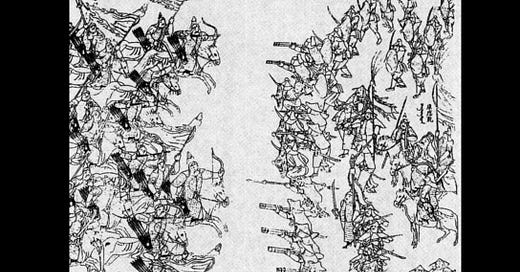

(Pictured: Manchu heavy cavalry attacking Ming arquebus soldiers, 1619)

This is part 2 of a series. See Part 1: The Song Military - and Part 3: The Qing Military

For a related essay on the Ming military, see The Ming Response to the Mongol Threat

In part 1, the Sonoma Sage described the Song Dynasty’s deliberate policy to create a large, but poorly led army. The Ming attempted to fix the Song’s solution but without long-term success.

The Ming Solution

The Ming leadership emerged out of the lowest class of Chinese society. Zhu Yuan-zhang - the future Hongwu Emperor - was born to a very poor peasant family. When he was a teen-ager, around 1343, his parents and all but one of his brothers and sisters died suddenly. These deaths were almost certainly due to the early outbreak of the Black Plague which swept across Europe just a few years later.

Note: as of 2022, ground zero for the Black Plague has been identified as a village in Kyrgyzstan in 1338. At that time, all of Central Asia was under the control of one of the Mongol Khans, just like China was. It seems fair to say that Black Plague was able to spread east into China and west in Europe, thanks to the Mongols.

Young Zhu Yuan-zhang was reduced to abject poverty and his life for the next four years is uncertain, many years later he was called the Beggar Emperor though no one can say what he did to survive. When he was 23, he became a war leader for the Red Turbans, an end-of-the-world Chinese cult. As he rose rapidly through the ranks of the Red Turbans, he recruited a group of men from his home village and more than ten of these men became his generals - victorious in battle after battle. The wars of the early Ming lasted from 1352 to 1368, at which time Zhu Yuan-zhang claimed the title of Huangdi of China. The fighting didn’t stop as the Ming had a special - and justified - hate for the Mongols who had caused so much death, misery, and destruction in China during their nearly 100 years of misrule.

The new Ming Huangdi believed that the Song practice of fielding a huge army with idiots as leaders was a terrible policy. The Hongwu’s idea was to create a hereditary class of military officers, the sons and grandsons of the men who had led his armies so well on his rise to supreme power. These hereditary officers would be loyal to the Imperial family by the bonds of honor. Additionally, they would be heirs to a glorious military tradition, and so they would be dedicated military officers. This was a characteristically Hongwu idea: he correctly identified the problem, and his solution - though clever - didn’t work after 75 years.

In practice, the hereditary officer class, after just a couple of generations, proved to be unmotivated and not very capable, though there were a few notable exceptions (see Qi Jiguang). Some families with this hereditary military service obligation illegally adopted one boy from a poor family to fulfill the requirement of sending one son into military service. Other families changed their names to escape the duty.

The Hongwu Huangdi also attempted to elevate the status of his military officers by giving them ancient titles of nobility such as existed in Tang Dynasty (such as: Gong 公, Hou 侯, and Bo 伯). However, the Hongwu Huangdi sabotaged his own efforts by ruthlessly demoting and often executing his generals for trivial reasons. Not one of his great generals survived the many purges of those who had helped place him on the throne - a massive character flaw in the founder of the Ming Dynasty.

Further, the idea that excellence in military leadership was an inherited trait was completely mistaken. Good military leaders are the product of motivation, training, and circumstance. After all, none of Zhu Yuan-zhang’s friends had a military background, they were all the sons of peasants, so far as we can tell.

A Mixed Record of Military Success

However, despite these problems, the Ming often fielded effective armies. The Ming army which rushed into Korea and defeated the Japanese invaders in 1593 and again in 1587 was well led and well supplied. The Ming’s heavy artillery battalions shattered the Japanese defenders in battles like the capture of Pyongyang in 1593. The Ming navy - fighting alongside the famous Korean Admiral Yi Sun - sank hundreds of Japanese ships and ultimately caused the large Japanese army to retreat ignominiously (See Ken Swope’s book A Dragon’s Head and Serpent’s Tail for details).

However, from 1600 to 1644, the Ming army was commanded by a succession of terrible leaders. A massive Ming army, more than 100,000 strong, suffered a humiliating defeat in 1619 at the hands of a Manchu army less than half it’s size, expertly led by Nurhaci (see the Battle of Sarhu). Later, the Ming were completely unable to stop four major raids by the Manchu armies under Hong Taiji in the years 1630-1642. In 1642, the Ming armies were defeated by the rebel army of Li Zhicheng. Li’s rebel army captured the capital city of Beijing, in the spring of 1644.

What Happened to the Ming Army?

First, by 1500 the old Song Dynasty system had largely returned. Meaning: the command decisions and campaign plans came from the Ministry of War, while the generals who actually fought all their lives had only slightly more input than they had during the Song era. We do see somewhat more give-and-take between the ministers of war and the generals of the Ming army, but only a little. Li Hualong (actually a provincial governor) expertly handled the destruction of a very wily tribal leader who had taken over southern Szechuan province in the Bozhou campaign (1599-1600). The civil-military cooperation during the Korean war was also effective.

Second, the Ming army became a paper tiger. Top leaders - generals and officials in the ministry of war - misused funds for the army to become wealthy. Weapons and armor which should have been made and distributed to the soldiers were often fictional and the money was instead diverted into buying real estate or running shops. Soldiers who should have been training for war spent most of their lives working as farmers on land set aside for the military. The overlarge Ming army was usually unprepared to fight when war came.

Third, in theory the Ming were spending a great deal of money making new cannons and building arquebuses for their soldiers. In practice, they did not. The Ming knew about modern cannons and arquebuses from Jesuits like Matteo Ricci. Further, they had seen them in battle as a result of their war with Japan in Korea. Japan’s ruler, Hideyoshi, fielded a modern army, thanks to the extraordinary leadership of his predecessor, Oda Nobunaga. However, the Ming modernization effort was mostly smoke and mirrors. When Li Zicheng’s rebel army arrived at the walls of Beijing in 1644, they should have been met by the Ming’s best army: 80,000 strong, all armed with the latest guns and cannons. Instead, the elite Ming capital army was no more than 3,000 men with an additional 25,000 men who were unfit for battle but who had bribed their way into the capital army as a way to get rich. Cannons and arquebuses either didn’t work or there was no ammunition (see Ken Swope’s book: The Military Collapse of the Ming Dynasty, chapter 7).

Conclusion

The Hongwu Huangdi’s strategy of creating a quality military by relying on specific families maintaining military valor and honor over many generations was not successful. True, it worked better than the Song and the defeat of Japan by the Ming army in the Imjin war - 220 years after the Hongwu Huangdi set up his system - was impressive. As the reader will see in the concluding essay, the Qing Dynasty started out strong but 200 years later, their armies were also paper tigers.

Perhaps there simply was no solution for China? The People’s Liberation Army has not accomplished much since the war they fought with the USA in Korea in 1952-54. China’s war with Vietnam in 1978 was not a war either side talks about, even after the passage of 44 years.

This is part 2 of a series. See Part 1: The Song Military - and Part 3: The Qing Military

For a related series on China & the Mongol Threat - see China vs. the Northern Barbarians- part 1.