Japanese Ninjas are pretty well known in the USA and Europe thanks to novels like James Clavell’s magnificent book Shogun and many recent Japanese anime, like Naruto. However, it has long been said - by everyone - that the Japanese invent almost nothing. From the Kimono (from China), to the Tea Ceremony (from China), to Samurai (likely from the kingdom of Silla in Korea) and on, and on, much of what is now thought to be Japanese actually came from some other nation.

Could the same thing be true about Ninjas? The Sonoma Sage thinks - Yes.

There are a number of reasons to think the Chinese had a professional class of assassins who survived in the shadows of Chinese society for more than a 1,500 years.

We know for certain of at least two unsuccessful attempts to assassinate Shi Huangdi (now called Qin Shi Huang). These took place around 230 BCE. Both attacks were dramatized in recent films, one called The Emperor and the Assassin.

We know that several unsuccessful assassination attempts were made on Cao Cao - the great warlord of the Three Kingdoms era. Other warlords from that time were assassinated, such as Sun Ce.

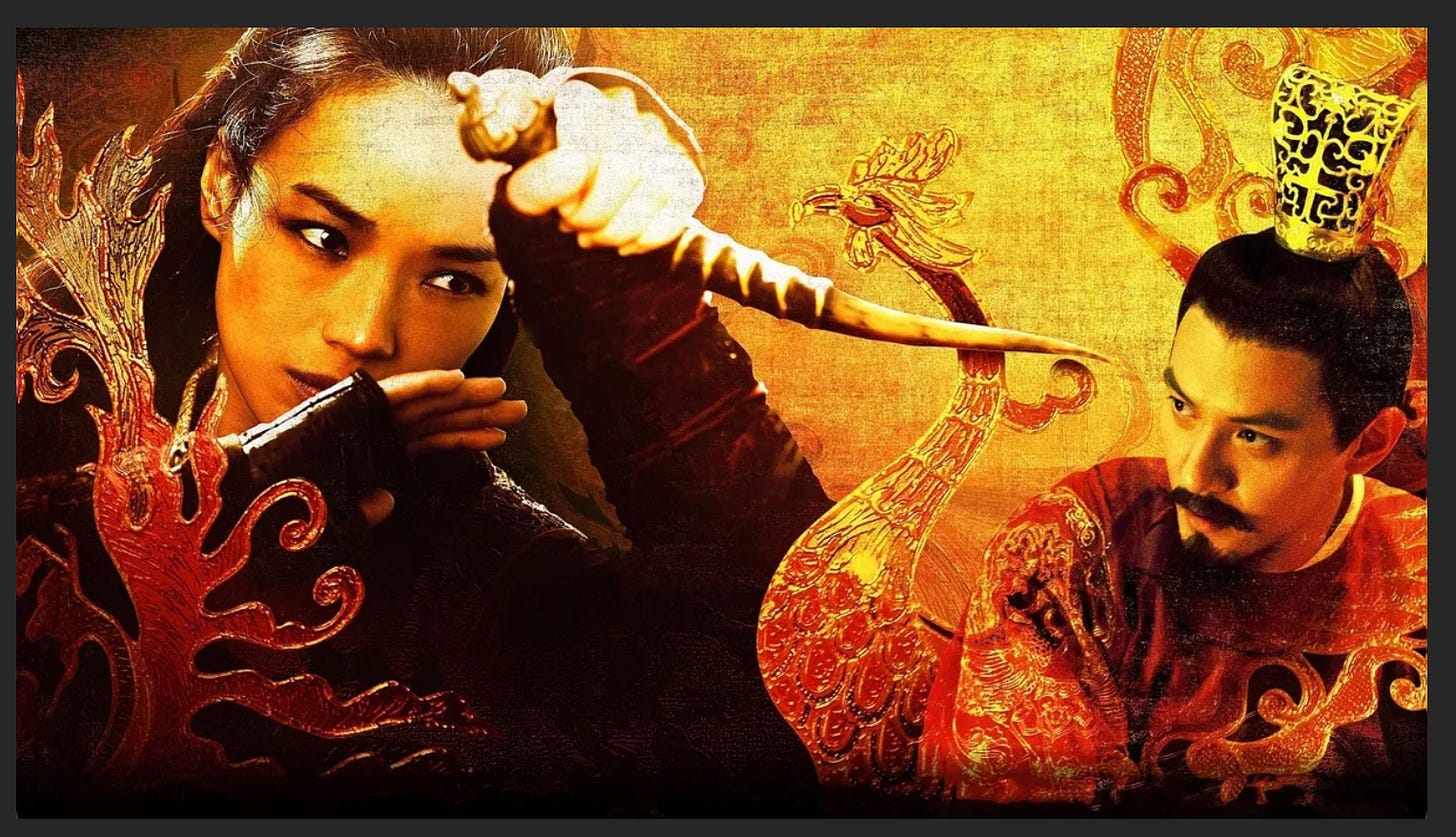

We know that one of the common characters in Chinese Theater was the Cishidan - the female assassin character. The Sonoma Sage has written about the incredibly odd film about a female assassin character. The movie is based on a brief biographical sketch about the real person from the Tang Dynasty.

These are facts. Suggestive but not much more.

Some of the Odd Coincidences in Chinese History

These are some of the odd coincidences which took place in Chinese history.

An Lushan’s Rebellion - The rebellion by An Lushan (755-763) nearly destroyed the Tang Dynasty and damaged it so badly that it really never recovered. The Sage won’t go into the details but the strange part about the story is: An Lushan revolted, defeated the major Tang loyalist army, captured the capital of Chang’an, and essentially forced the Huangdi (Chinese Emperor) to cede his throne to the eldest son. This looks like a victory for An Lushan. But just six months later (early 757), An Lushan was dead, murdered (we think) by his long-time eunuch aide, supposedly acting under the orders of his An’s son Qingxu.

Two years later (April, 759) An Qingxu was himself murdered at the orders (we think) of one of An Lushan’s longtime generals, Shi Siming.

A week later, Shi Siming was himself murdered at the orders (we think) of his own son Shi Chaoyi. Four years later, in 763, Shi Chaoyi’s army was scattered and defeated and he committed suicide, so bringing an end to the rebellion.

This sequence of events seems remarkably convenient for the Tang Dynasty. It could just be a coincidence that the rebel leaders were killed by people very close to them. But it seems equally likely to the Sage that these murders were performed by Tang assassins and the rebels painted a different story on the events to keep their army’s moral from plummeting.

Another series of odd deaths occurs in the time around the Ming Dynasty’s collapse (1642-1652). The Sage commented on this in his essay about Prince Dorgon. To recap:

Hung Taiji, the ruler of the very successful Manchu state, victorious in all his campaigns, dies, quite suddenly and from no known disease at the age of 50 in 1643. To be sure, he had fought in many battles earlier in his life but he had been the Huangdi of Qing for the last eight years, his warrior days were long past. His death should have caused enormous trouble for the nascent Qing kingdom as there was no obvious successor and no standard formula for choosing the next ruler of the Qing state. If the Ming could have assassinated Hung Taiji - they absolutely would have. The reality is, the Qing Kingdom was growing rapidly, and many people joined who had been Chinese - even highly ranked Chinese officials in the Ming government. No doubt most of these men and their families were loyal to the new Qing state, but were all of them?

Prince Dodo, dies, quite suddenly, at the age of 36, supposedly from smallpox (in 1649). Now Dodo, like all the Manchu leaders, was extremely worried about catching smallpox because very few of their family members who caught smallpox survived. The Manchu - for unknown reasons - were particularly susceptible to this disease. Prince Dodo, one of the ten most powerful people in the Manchu state, and younger brother to the most powerful man, should have been able to protect himself from smallpox infection - unless someone deliberately attempted to kill him. Dodo’s death was very convenient for the enemies of Prince Dorgon.

Prince Dorgon dies just one year later, at age 38. His death is highly suspicious and was always thought so. Dorgon died as a result of a leg injury he sustained while he was out riding. True, leg injuries can kill, but Dorgon was an expert horseman, and a veteran of military campaigns since he was 10 years old. Further, his death was extremely well timed. The Shunzi Emperor had just recently turned 13, the age at which a Regent was no longer required. Thus, when Prince-Regent Dorgon died, the Shunzi Emperor was able to take over the government in his own name. In reality, he wasn’t in control, instead another Manchu leader - and former regent - Jirgalang - stepped into Dorgon’s role as the defacto ruler of the Qing government.

Lastly we have the somewhat mysterious death of Wu Sangui in 1678. Wu Sangui is an often reviled figure in Chinese history as he joined forced with the Manchu in 1644, then led his army in military operations against members of the Ming royal family as they tried to rouse the people and throw the Manchu out of China. Wu Sangui’s armies were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Chinese Ming loyalists.

Having served the Manchu - the Qing Dynasty - so loyally, after twenty years he took up arms against the new Qing ruler, the great Kangxi Emperor in what is called the Revolt of the Three Feudatories (1674). Wu Sangui had significant success but when he declared that he was now the new Huangdi of China, his days were soon ended. Wu Sangui, died “of illness” just a few months after his claiming the throne, at the age of 65. Dying at 65 in this time is quite common, but the timing is odd. Wu Sangui has been fighting - and winning - against the Manchu for more than three years. He claims the throne, and then dies just months later?

Conclusion - The Chinese Assassins were Real

The Sonoma Sage believes, based on the weight of evidence, that for more than one thousand five hundred years, the Chinese state has had a secret society of assassins, operating just outside of official channels. Never documented, the Sage guesses the orders given to these assassins were always issued verbally. The Chinese assassins seem to have been most skilled at killing people who had recently taken the mantle of Huangdi - which suggests that the assassins were likely trained as palace eunuchs or were women trained to put poison in food and drink.

The Sage further guesses that some of these assassins moved to Japan at some point, offering their services to the Japanese Tennos (the Emperors of Japan), and later, the Shoguns.

The Sage does not think that any proof of this theory will be found. The Confucian scholars would have been disgusted to associate with eunuch assassins and apparently no records document any such association between the Imperial Court and a band of assassins.

The Sage believes that stories about eunuch assassins first appeared in films made in Hong Kong in the 1960s. The Sage himself saw several such films but he can no longer remember the titles of the movies.